This is my transcription of an interview of Professor Joseph Tainter by Aengus Anderson on August 7th 2012, at that time I had authorization by them to publish it in a blog. It's not pretty new, but it's still fundamental to enlight our understanding of the world. The audio is available at

http://www.findtheconversation.com/episode-nineteen-joseph-tainter/

together with a short presentation of the talk and of the author.

JT: My background is in anthropology, that’s what my degree is, and my passion, since I was very young, was to be an archaeologist, and so within anthropology I specialized in archaeology and I went through the courses I studied and I worked various areas for quite a few years, but I always had a curiosity also in contemporary issues and I thought that it should be possible to use what we learned about the past to understand our situation of today and the future. In the 1980’s I began a study of a topic that had entreat me for a long time: why did ancient societies often seemed to collapse, and by collapse I mean why do they seem to simplify rapidly, think about the western roman empire collapse and being succeeded by the dark ages in the western Europe. As I did that study in the 1980’s, I began to realize that I was learning was not just about the ancient societies, it has values for us and for our future. Gradually in the following year I began shifting more and more into working on sustainability and particularly how can we use lessons from the past to understand whether we can do to be in a sustainable society today. I worked largely on complexity, on energy and most recently on innovation. Energy and innovation are really the two key elements to sustainability and interact with complexity, to make a society sustainable or not over the long term.

AA:Talk us more about of complexity. What do you think when you talk about complexity.

JT: My understanding of complexity really comes from within my background in anthropology. Complexity in a society means first of all more kinds of parts, but particularly different kind of parts. So you think in a simple hunting and gathering society, where generally there is very low specialization. A few people are better in something than others, but by enlarge the main social roles are defined by age and gender: males, females and children and those are the main three social categories. You compare that to how specialized our society is today, you can recognise something as many as 40.000 different kinds of occupation, we are a highly differentiated society, many different kind of specialization, many social roles, very very differentiated technology. This is what I mean by the term structure of differentiation. That’s one aspect of complexity, but is not the only one. The other aspect of complexity is organization, the parts have to be integrated together to make a functioning whole, they behave in patent and predictable ways. You cannot have people in a government bureaucracy simply doing whatever they want, they are told what to do. People within a family has certain specific roles that are expected to fulfil and if you step out of this roles there are usually consequences. This is organization. Complexity consists of differentiation and structure along with the increase in the organization. The organization existing to make everything functioning as a coherent system.

AA: So what are some of the reasons we have seen these earlier civilizations collapsed?

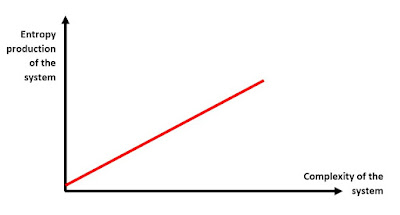

JT: Societies grow more complex, because is one of the most fundamental ways simply to solve problems. Complexity is actually a problem solving tool. Let me give a couple of examples from my experience of today. After the terrorist attacks of September, 11, 2001 how do we respond? Well we created new government agencies to perform for more security, transportation security administration, we reorganized other agencies, so in another words we differentiated structure, we created more structure in our system, and at the same time we increased organization, that is to say we increased constraints on behaviour, behaviours that we thought would be threatening so now we all stand in line to get into our flight at the airport, to channel behaviours make behaviours uniform and predictable. We increased complexity to respond to the threat of terrorism. The problem with becoming more complex is that complexity is never free. In any living system complexity has costs, it has a metabolic costs. If you think of, in the natural world, the complexity of say a simple bacterium versus the complexity of man or a deer, the man or the deer are a more complex organisms and they have a much higher energy requirement as a result, not just relative to body size, but disproportional to the body size and that is because the warm blooded mammals they regulate they internal body temperature and they reproductive systems and they need extra amount of energy to accomplish this. Is the same in human society, you cannot have higher complexity without having a higher energy base, and it tends to grow almost unnoticed and it grows by small increments each of which seems reasonable and affordable at the time, but over time the complexity and the cost build up and, as I told you, they reach the point when you get into diminishing return and this is the point where society start to become voluble and collapse, where you are spending more and more to get less and less.

AA: Does it seem inevitable to you?

JT: Yes, growing in complexity is inevitable and I think that reaching the point of diminishing return of complexity is inevitable. Now I will give you an example o how this works on a natural societies: the collapse of the western roman empire. Agrarian empire can only expand so far, in the last few centuries B.C. the Romans expanded throughout the Mediterranean basin and into North Western Europe and every time they did so, they essentially loot the province they conquered and what they were looting was stores of past solar energy, which was transformed into precious metals, works of art and people. And they then use this, first of all they eliminated taxation on themselves, and they used the wealth to find further conquests, it was a nice positive feedback loop, but it can only go so far. Eventually into a growing society that doesn’t have modern communication, that doesn’t have modern transportation, you reach the point where you simply have to higher travel distance to the frontiers and you eventually encounter people who just doesn’t want to be conquered. So the roman empire reached this point about the first century A.D. and then they had to transition from living on stored solar energy, which is the accumulated solar energy by the people they conquering, and to live on purely solar energy. In other words purely agriculture, the roman empire was primarily an agricultural economy, 90% of the government taxes came from agriculture. So beginning in the first century A.D. and thereafter the government essentially had to live of a current solar energy budget. And this immediately began to cause problems. Well, in 64 A.D the Romans where facing a dual crisis: one was the war on the east and the other was the great fire of Rome, when Nero was supposed to burn Rome. And suddenly they did not have enough precious metals on hand to cope with those crisis so they began to debase the currency by heading in copper and this was the first step down the slope. They resulted ultimately in 69 A.D. with the currency that had no silver at all, they can sustain their own going expenses only by debasing the currency, which effectively is a way of shifting costs on to the future. This is very important, because it is less as for us today. In the third century A. D. they faced a set of crisis, a set of crisis that almost brought the empire to its end, there where invasion of the Persian from the east, the German people from the north, there where civil wars, there was unrest, there was banditry. In the late third and early fourth century a couple of reforming emperors rescued the situation: Diocletian and Constantine. First of all they double the size of the army, but they also increased complexity, they differentiated financial functions within the bureaucracy, they increased the size of bureaucracy, the empire had to entertain this increase of complexity at a great cost, and it worked: they survived the crises and essentially keep on sustainability for another two centuries, so the sustainability of the empire and the Greek-roman civilization, which was their goal. But the cost was that they had to increase taxation on the peasantry, so you here reports peasants being unable to pay taxes, peasants abandoning their lands, so the empire essentially went from living of interest, which was yearly agricultural production, to living of its capital, its capital being producing land and peasants population. At the same time, the increase in complexity didn’t bring any new net wealth; it was simply to maintain the status quo. And the time made it physically weaker and weaker and finally in the end they began to lose more and more provinces and then the last emperor was overthrown in the year 461 A.D. This is the challenge happened to the roman empire.

We can see several parallels to our situation today, when the Romans went from an economy based on seizing the past solar energy the people they conquered to an economy based on current solar energy that’s now I guess to what may happen to our future when we go from living on stored solar energy, which is what fossil fuels are, to renewable energy economy, we have to live on annual solar energy. The Romans found they could not do it. So they were force to debase the currency, debasing the currency for them was the same as borrowing is for us. It basically shifts the cost of solving your problems onto the future. You can do that if the future has no problems of its own, but we know that never happens. So the future has to deal with its own problems plus the cost of the past problems that you divert the cost of. The other way in which this informs us about whether our future may look like is increasing in complexity just to maintain the status quo. I see a set of constraints facing us in the future and they are all going on being very expensive:

- Retirement of baby boom generation

- Continuing increase in the cost of healthcare

- Replacing decay of infrastructure

- Adapting to climate change and repairing environmental damage

- Developing new sources of energy

- Continuing high military costs

- The cost of innovation

We are going to have to invest into each of these areas mainly just to maintain the status quo. And this are all problems that are all to converge over the next generation, basically over the next 10-30 years or so, which historically is more or less simultaneously. This is exactly the same problem that was teasing the Romans, having to increase complexity and cost just to maintain the status quo. It brings to diminishing returns and physical weakness, I think it will bring us to a situation where people incomes do not grow, people of the USA and other industrial countries we are accustomed to, and this will bring on political discontent, the political discontent we have in this country now I think is nothing compared to what maybe see in the future.

AA: Is there some way to recalibrate expectations?

JT: I’m not an idealistic when I come to that. I sometimes think I know too much history, I think I understand the species very well. People would not voluntarily refrain from consumption they can afford on the base of abstractions about the future. If people don’t experience problems in their daily life, they would simply continue spending whatever they can afford, or consuming whatever they can afford. Economists tell us, and in this point I agree with them, that what change people behaviour is the price mechanism, that is what can cut people consumption.

AA: How do people expectations go away? How do you recalibrate expectations?

JT: I think it takes a generation at least for expectations to change, perhaps even two generations. And this is one of the immediate problems that I see over the next generation, is simply high level of political discontent over the economical problems we are going to being facing. You can see this happening in Europe with the Euro-crisis where leader after leader after leader has been thrown out of their office in Greece, Italy and France. In this country of course president Obama faces serious challenges for the economy and he may very well loose because of that.

AA: Does the discontent become a sort of self fulfilling prophecy? There is enough political discontent expressed that it leads to policy that actually continues to undermine the complex system? I’m kind of wondering about the point where things start to going down hell.

JT: The discontent I think it leads to turmoil, and to continue to change over policies. I can foresee a situation where we may just cycle very quickly back and forth between republicans and democrats as far as is in charge. Because of one is in charge for a while and then fail, and then will turn the other one, and then fail. Whereas in fact it maybe no policy can solve the problems, that we are simply growing to the point where we are too complex for the energy basin we can expect to have in the future, because this is all tight to the availability of fossil fuels. We are reaching, or we will soon reach or we may even have reached the peak of the production of fossil fuels. And this is going to mean that is going to be harder and harder to generate the wealth that we need to solve our problems.

AA: I spoke to an oil industry analyst, and he thinks we have already slightly hit peak oil. Other people I spoke into, see space as a solution. Is space the next end up wealth of resources that could unleash....

JT: That’s a wishful thing. That’s a kind of thing children think about. We cannot afford space program have now! I could we ever afford programs that let us allow resources from space.

AA: You don’t buy the silver bullet coming in from science solving our problems.

JT: Well, that’s a different matter. Technological optimists and commercial economists thinks this also, that as long as we have free market and the price mechanism there will always be incentivs to innovate and that we have not to be worried about resources. There always be either new resources or more efficient ways to use old resources. There a couple of problems with technological optimism, the first problem is what is called the Jevons paradox. William Stanley Jevons was a 19yh century British economist, very well known about economic history. One of his books was called “The coal question”, Jevons was concerned that Britain would lose the pre-eminence in the world because of the exhaustion of coal, of course he couldn’t foresee the future of petroleum, but he enunciated several principals that last in value for us today. He looked at the improvement in technology of the steam engine, so that they can get more and more out of each ton of coal. The expectation was that this would mean that Britain be using less coal in the future. Jevons said: no, what will happen is that the price of coal will be reduced so much that we will simply use more than ever before. There is new improve, the efficiency of the use of a resource actually increases rather than decreases. Well that was coal in the 19th century. Look at our more recent history, particularly at the oil crises in the USA in the 1970’s, with major increases in the cost of oil in the 1973 and 1979. This led manufacturers to introduce more and more fuel efficient cars to the American market, and consumers bought them. So, how did consumers respond to have more fuel efficient cars? Did they save the money? No, they drove more miles. This is the Jevons paradox. This is one reason why improving technical efficiency has only certain benefits. There’s also a problem with innovation itself. Innovation is also a system that grows in complexity and reaches diminishing returns. Basic discoveries like gravity and electricity no longer are them waiting for us to find them, instead, while once innovation could be done by scholars or Charles Darwin or Henry Ford is now done by very large interdisciplinary teams that require very large budget and large institutions to work within and it is producing diminishing returns. Some colleagues and I did study a couple of years ago on the productivity of our system of innovation as is reflected on patents. What we found is that over the last 30 years our system of innovation is declined in productivity by 22% and there is no reason to think is going to end, and it is pursuing in declining because of increasing in complexity and cost in knowledge production. And so you see for example pharmaceutical companies that are withdrawing from innovation, the research and development is becoming less and less profitable to innovate because is becoming harder to innovate.

AA: And do you think that is because of the scientific point that we reach or is there a social and economic system that discourages that sort of small scale?

JT: No, no, I think that is primarily because it is simply become more complex to produce new knowledge. People generally don’t see this because when you go to electronic stores there are always new products, but the reason we keep evidence on new products is because the scale of the innovation enterprises has grown so large, we spend more and more resources on it. A number of years ago congress doubled the budget of the national institute of health, doubled the budget of the national science foundation, but this is what’s necessary, you have to keep not only spending more and more to innovate, but you have to spend a large and larger share of economic pie on to innovate and at the same time productivity, which is measure in patents per inventor, is being going down for at least a generation and there are indications that may be going down even longer than that.

AA: If I can bring in one of the other ideas, the idea of futurism. Essentially, for those thinkers they think increase in complexity as a high privilege, like going from chemical and simple organism to increasingly complex systems.

JT: Personally I feel that when your narrative about the future includes phrases like “a miracle happen”, you’re in trouble. That would be my short answer. Of course we can roll up the possibilities, something could happen in the future that none of us can foresee it, always possible, or we can deal on what can be reasonably foreseeable.

AA: Working in the world of the things that are reasonably foreseeable, we talked about the crisis of the present, and the idea that in the next 30 years we could have a storm of all these different things coming together. Do you see that is leading to collapse, or do you think that would be a sort of a momentary thing and we act can develop more complexity. There some people in this project that think that is something pretty near term and something that means to be discussed now.

JT: Right now I’m thinking one or two generations in the future. I don’t think we are in an immediate danger of a collapse. But looking in 30 to 60 years now I’m very concerned about how the future may evolve. Given declining supply of fossil fuels, particularly oil, given declining productivity of innovation, I think expectations of continued economic growth are problematic. The government might be able to spur more economic growth with stimulus plans for a while that simply shift costs onto the future. I’m not optimistic about continued economic growth definitively into the future, is going to be impossible. Renewable energy sources simply do not give the energy density and return on investment that fossil fuels give us, there’s nothing like energy density in a gallon of gasoline and that is the basis of our wealth. We think we developed our wealth through ingenuity and hard work and certainly our engineer worked hard but this would have not any meaning without cheap fossil fuel sources. People from the past were ingenious and worked hard, we have pull ourselves up by employing fossil fuel subsidies, and that is what we pay for complexity today. So, what does that leave us for the future. It leaves us with the possibility of what is sometimes called a “steady state economy” or a collapse. The problem with a steady state economy is that many people will find it not acceptable: steady state means steady state, birth rates have to equal death rates, which means you can have only a child. It means that if someone ascends the economic someone else has to fall down. So a steady state economy I think has potentially serious political problems. So, where is the alternative, it is simply to try to keep forcing growth? Until we simply do not support complexity anymore? In which case we simply be vulnerable to collapse. I don’t have a crystal ball, I don’t know what is going to go, but I’m very concerned.

AA: Why is collapse so bad?

JT: A collapse in our near future probably would mean that hundreds of millions of people would die. It will be gruesome, it will be a horrifying thing. Is not something we want to go through. If we could rapidly find a way to gradually reduce the earth population, in the next century or so, if everyone voluntarily agree to have only one child and of course this is not going to happen, then a collapse might not be so bad, but it will be a wrenching change in people way of life. 90% of us would have to be a farmer, higher education will once again become a preserve of only the wealthy, and an economy like that has very serious implications. It will mean, that we would lose a lot in our way of life that in fact valuable, the ability to be rewarded for one’s work, proportionate to one’s work, the ability to be rewarded for good ideas, the ability to move to wherever you want to live, the ability to find interesting books to read, these are all things that we would be lost in a collapse. The dark ages were dark for a reason. A collapse is really not a desirable thing.

AA: I’m thinking on the conversation I had before, for him the collapse is a desirable thing. He has a different metrics for measuring it, he says yes all of these things will go away, but we are living in a society that is so hyper individualistic, there are things that have a disproportionate meaning, and if you have a collapse maybe you will have stronger relationship with you community, you have a greater sense of connection with people around you, you have a sense of connection with the earth, is there anything good in that?

JT: Sure, all of these are valuable things, but they are the only valuable things. Speaking only for myself I enjoy a life where I can sit in a room speaking with young people and talking about bright ideas, talk philosophy, teaching about complexity, talk about history and think about our future. These are things that I value, and I value having the kind of society that we do, because it provides opportunities to do that. And we can take that example, my own experience and we can multiply it many and many times for all the different things that people do. In a society in which 90% of us have to be farmers most of those things will go away, being a farmer is an admirable calling and wonderful thing, my wife and I own a neighbourhood of land in new Mexico where we cultivated firmly intensively, I love farming, but it is not just what I want to do.

AA: To what extent can a conversation change everything?

JT: When people ask me what has to be done, I always say the first step is awareness. And that is what this conversation is about, that’s why I do interview like this one. But at the same time I recognise that I reach very few people in doing this kind of interview. What has an impact and affect people’s daily life, and that’s why I say it is going to change people’s behaviour, is the price mechanism. In the human evolution there was never selective pressure to think broadly in terms of either time and space, and so humans don’t. We are simply not inclined to by nature. A few people do, but they are a rarity. I don’t know whether this is changeable, I have actually written about this, wandering whether if we could start very early in our educational system, if children could be taught to be more curious about things that are distant in time and space, I like to be a little optimistic to think that humans can learn to think different and after all we didn’t evolve to live by clocks. So humans can learn, but it involves I think some fundamental changes in education. And if I was 30 years younger but I knew what I know now, I might spend a lot of time talking with educators. But I’m not a kind of educator even myself, so I don’t really know how you reach children at that age, how to teach them to think different about broad scale matters. But it is something we have to do, the future depends on it. Conversation is important but I don’t know whether conversation is enough.

AA: Is there a change in the air, or is there a exchange of ideas between people of diverse background about the future, that you are aware?

JT: Well, how may the people shopping if they would be aware of what we are talking about . That’s my answer to your question. But all we can do is to try, we have to try.